‘to help create a non-dogmatic, non-religious, non-bullshit Marxism’ (Tariq Ali on Daniel Bensaid, 2013)

by Dr Jones Irwin, Institute of Education, Drumcondra, Dublin City University.

to accompany workshop, details below

1967. 50 years ago this year and it was the year that Guy Debord published his infamous text Society of the Spectacle. This wasn’t exactly the beginning of the Situationist philosophy. Rather, the latter had emerged in disorderly fashion some ten years earlier in a remote north Italian tavern. This wouldn’t be the last time this vision would relocate from France to Italy and back again. Gianfranco Sanguinetti’s ‘The Real Report on the Last Chance to Save Capitalism’, an incendiary satire on Italian politics (influenced by Machiavelli) would see him deported from an unstable and Red Brigade Italy in the 1970s – to where? France of course.

Should we still be reading Guy Debord or encouraging others to read him politically for the first time in a contemporary context? In popular culture parlance, Debord’s name will always be associated with the political moment of May ’68, the general strike and the student riots which spread from the campus of Nanterre (led by philosophy and sociology lecturers Jean Francois Lyotard and Henri Lefebvre). And rightfully so. Whereas the much vaunted Marxism of Louis Althusser (alongside his soon to be famous students Rancière, Badiou and Balibar) is left completely behind by the explosion of ’68, Situationism and Debord are right at the heart of it, there at the beginning of its genealogy from 1965 onwards and present in its most acute and radical manifestation in May.

So the Situationism of Debord has at least this advantage over a lot of other so-called radical political and cultural theory. It was influential on and participant in an actual extraordinary moment of political and social upheaval, although the sustainability of this moment did not last long. For this reason, it should be at least of historic value and interest.

But I would like to claim some more interest too. Since 1968, the terrain of political thinking both on the Left and the Right have been irrevocably marked by the failure of ’68. Therefore, alongside the role of Debord in the lead-in to ’68, there is also the question of the role of Situationism in what Kristin Ross has referred to as the ‘afterlives’ of ’68. For example, there is the emergence of a specific kind of right-wing philosophising in Luc Ferry and Alain Renault which takes as its target precisely the anti-humanism of Debord and others. This strain of thought is very influential on French political life, for example through the influence of the educational policies of the Raffarin government (2002-2004), where Ferry served as Minister of Education. One of the most influential policies introduced at this time was the law on secularity and public rules around religious symbolism and expression, which continues to be highly contentious in 2017.

There is also the converse influence – from Rancière, to Badiou and Balibar, the ideological turning away from Althusser’s Marxism towards a political and educational vision that is far more radically democratic and anti-vanguard elite. This political-philosophical vision owes a significant amount to Debord’s earlier iconoclastic vision of the Left and a renewed Marxism for the times, expressed vehemently in Society of the Spectacle. Moreover, it is arguable that the current political crisis of meaning, whether it is the post-truth discourse of the Trumpist Right or the sense of internal schism on the Left (most especially concerning questions of religion and multi-culturalism) is one in which Situationism may have also something interesting and unique to contribute. Whither in such a schismatic context the critique of ideology today? It is my sense that Debord’s work as well as the wider Situationist vision (Vaneigem, Lefebvre etc.) has something contemporary to say to us in this debate. To quote a ’68 graffiti adapted (as many of the slogans were) from Debord’s and Situationist texts: ‘the blue in the sky will remain grey as long as it is not reinvented’.

This presentation will focus on Debord’s role in the ’68 events through a reading his Society of the Spectacle text. It will also explore the after-effects of ’68, the seismic fall-out of the so-called ‘failure of May’ and here Debord’s own retrospective understandings will be invoked, for example in his 1988 text Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. In this context, the influential volte-face of Jacques Rancière’s later political and educational thinking post-68 will also be significant. Rancière’s unequivocal denunciation of Althusserianism and dogmatic Marxism in Althusser’s Lesson (1974) and his later The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1984) are important milestones in Leftist rethinking of the terms of reference of a contemporary Marxism.

Finally, I will look to contemporary examples of Situationist possibility. Here, my own recent work in Irish education (for example, developing a Multi-Belief Values Education curriculum with Community National Schools) will be cited as an example of a kind of Situationist intervention in an overarchingly hegemonic system of dominance by Church and conservative power interests in Ireland.

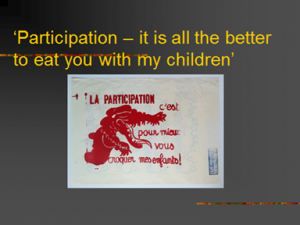

Nonetheless, and in keeping with Debord’s radically self-questioning spirit, we should also be wary of educational and political complacency in our supposedly ‘liberatory’ projects. As another ’68 graffiti has it, ‘Participation, all the better to eat you with my children’ [‘La Participation, c’est pour mieux vous croquer mes enfants’]. There is always the danger lurking, Debord reminds us incessantly, of complicity with traditionalist forces and the commodification of supposed resistance or revolutionary zeal by the Spectacle.

Bio

Jones Irwin is Associate Professor in Philosophy and Education at the Institute of Education, Drumcondra, Dublin City University. Since late 2014, he has also been seconded as Project Officer to develop the first state multi-denominational curriculum, with NCCA. He has written several books in philosophy, including Derrida and the Writing of the Body (Ashgate, 2010), Paulo Freire’s Philosophy of Education (Continuum, 2012) and (with Helena Motoh) Žižek and his Contemporaries (Bloomsbury, 2014). He is currently completing a monograph entitled The Pursuit of Existentialism (Acumen/Taylor Francis 2018).

Dublin Political Theory Workshop

This blog was written to accompany a workshop by Dr Irwin for The Dublin Political Theory Workshop. This is hosted by UCD School of Politics and International Relations and brings together political theorists located in or visiting Dublin. We discuss work in progress in the area of political theory widely understood including debates on applied ethics and social and legal philosophy.

Dr Irwin’s workshop is on Friday, 27. October, 12:30 – 14:00

Title: Situationist Possibles: Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle Then and Now

Full schedule for Dublin Political Theory Workshop series.

Follow

Follow